Atticus Finch and Our Mythological Whiteness

Jul 17, 2015

This weekend, bookworms around the world (myself included) will sit down and eagerly crack open the recently published new book by Harper Lee, Go Set A Watchman. Fifty-five years ago last week, Lee published what would become a staple of school reading lists in the United States for generations to come, To Kill A Mockingbird. Watchman, though supposedly composed as a first draft of the story that would become Mockingbird, takes place roughly 20 years after the events of Scout’s childhood and Atticus Finch’s defense of the wrongly accused African American man, Tom Robinson. Gallons of virtual ink has already been spilled over reviewing this new novel and its literary significance or lack thereof, and it is not my intention to do so here. If you’d like a taste, you can read the first chapter online for free.

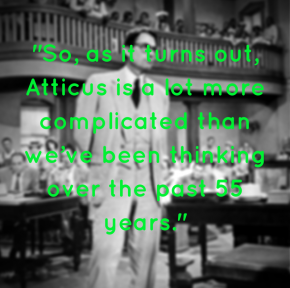

The news coming out of reviews that has frustrated many Harper Lee fans is the, apparently, markedly different portrayal of Atticus Finch, one of the most beloved characters of American literature, mainly for his valiant actions and impeccable sense of racial justice in the face of small-town Alabama’s violent racism. Atticus Finch represents more to us – and I would argue specifically to white people – than simply a well-rounded character in a classic novel. He represents the most hopeful aspirations we have of ourselves. It is important to remember, too, that when Mockingbird was published, our country was in the midst of a crescendo of social awareness about the injustices in the United States for people of color, particularly for African Americans. A character like Atticus Finch was a revelation not only to Americans in general, but to Southern whites specifically. For those of us with Southern roots, we practically idolize Atticus Finch. We even name our sons after him. And so it was with a mixture of surprise and disappointment when we learned recently that the author’s original draft of Atticus was as an outspoken segregationalist who reads propagandist literature by white supremacist organizations. So, as it turns out, Atticus is a lot more complicated than we’ve been thinking over the past 55 years.

However, I believe this is more complex than simply seeing the quintessential good guy in a new, ugly light. This is about how we white people view ourselves and our relationship with people of color in this country. This is about the standards we set for behavior and thought in a multiracial society. This is about the myth we have told ourselves about our whiteness.

The truth is that we are both Atticuses at once. We are the younger Atticus who sticks up for our friends of color when our white friends start to tell a racist joke in our presence. We are the older Atticus who awkwardly laughs at a racist joke the next day because speaking up would cost too much social capital. We are the younger Atticus who chants “Black Lives Matter” in front of the Ferguson Police Department facing a line of police in riot gear. We are the older Atticus who perpetuates subtle language about “good” and “bad” areas of town, knowing that it’s just as much about the predominant color of the neighborhood as it is about the crime rate.

I am currently the only white full-time employee at Diversity Awareness Partnership. I am one of maybe three white people on my whole block in Dutchtown in an overwhelmingly African American neighborhood. During a normal day, my everyday life is full of people of color. This is an exception. I also realize that this does not allow me to understand the lived experience of my neighbors and colleagues of color. It does, though, give me different insight than many white people I know. This insight has proven invaluable in diversity trainings, where I’m frequently asked questions that all come down to something like, “So, what are we [as white people] supposed to do about this? I’m a good person. I treat everyone fairly. I’m not a racist. I don’t understand how all these problems still exist.”

There are as many ways to answer this concern as there are ways to ask it. After nearly a year of examining my own privilege more deeply than I ever have in my life, I’d like to offer a handful of suggestions:

- Have conv

ersations about whiteness in white spaces. Interracial dialogue is crucial to understanding other perspectives. In fact, DAP is facilitating a whole week of these sorts of dialogues starting on August 3rd. The way that our institutions will begin morphing into more just versions of their former selves is if those of us who have traditionally held the power begin to challenge others of us who have that same power. Expecting people of color to be the only ones doing that is unfair at best, and propping up unjust structures at worst. We must use our privilege in order to create new dynamics where we can begin to lose that privilege.

ersations about whiteness in white spaces. Interracial dialogue is crucial to understanding other perspectives. In fact, DAP is facilitating a whole week of these sorts of dialogues starting on August 3rd. The way that our institutions will begin morphing into more just versions of their former selves is if those of us who have traditionally held the power begin to challenge others of us who have that same power. Expecting people of color to be the only ones doing that is unfair at best, and propping up unjust structures at worst. We must use our privilege in order to create new dynamics where we can begin to lose that privilege.

- Don’t settle for being enlightened. You follow the right blogs. You know the most insightful hashtags. You can articulate the difference between what it means to say“All Lives Matter” versus “Black Lives Matter.” All of these are fantastic starts to an important process of self-awareness of one’s own whiteness. Once you’ve determined that you cannot possibly “be racist,” though, the work stalls out. Continue to stay informed on discussions of race in our country. Ask a racially diverse group of friends and colleagues to literally hold you accountable for your words, behavior, and education. The moment we believe that the process of our self-analysis is complete, atrophy sets in. It is a move riddled with privilege that allows us as white people to say, “My journey of racial self-exploration is complete.”

- Be ok with making mistakes. None of us are perfect. Simply because you don’t know the latest vocabulary to talk about issues of diversity doesn’t make you uncommitted to this work. Not only should we be okay with making mistakes, we should be actively creating communal spaces for dialogue wherein mistakes are valued as steps toward learning. Moreover, don’t allow the emotional and intellectual discomfort to stymie your efforts. That discomfort is a cocoon that stands as a staging ground for an improved way of relating to our sisters and brothers of color. White fragility is to be avoided at all costs.

- Listen to experiences outside of your racial reality, and believe them. During almost every single training I facilitate, I hear at least one story from a person of color about getting unfairly and threateningly stopped by police, about getting treated vastly differently at work than their white colleagues, or about being called the n-word in public. These are real stories of real people undergoing real experiences. We must not dismiss these as one-offs. People are trusting us enough to tell us the traumas they are experiencing. We must not chalk it up to random bad guys.

When I was in college, I had the rare opportunity to interview the famous poet, playwright, and founder of the Black Arts Movement, Amiri Baraka. I was so incredibly nervous during the perhaps half-hour interview that I recall very little of what that titan in the history of American art said that day. I do remember, though, what happened when I asked him, “So, what needs to happen to improve race relations in our country? When is anything ever going to change?”

Mr. Baraka paused for a moment, stroking his salt-and-pepper beard thoughtfully, and answered, “When both Whites and Blacks realize that we are all controlled by the same ‘The Man,’ that is when things will begin to change.”

White privilege exists. It destroys us all, even and especially those of us who have it. But we cannot easily escape it. We must accept it before we can begin to change it. We are still both Atticuses.

Kenneth Pruitt, Director of Diversity Training